Avian flu, ebola and SARS have all made headlines in the past two decades, with catastrophic outbreaks of these deadly diseases claiming hundreds of lives. Comparatively, malaria often gets little to no media coverage. Yet researchers concur that it is likely the deadliest disease in human history.

Significant progress has been made in combating malaria, with the World Health Organisation (WHO) playing a pivotal role in raising awareness among governments and citizens in third-world countries on malaria prevention. These efforts have borne fruit, with malaria incidence declining by 21% from 2010 to 2015 and related deaths falling by 29% for the same period.

But more remains to be done. According to the latest available data from WHO, almost half of the world’s population remained at risk of contracting malaria in 2015, with 212 million new diagnoses and 429,000 deaths.1 Malaria is a preventable disease when simple and inexpensive precautions are taken. Every new diagnosis and every new death, therefore, is one too many.

What is malaria?

Malaria is an infectious disease caused by parasitic protozoans that are transmitted to the human body through saliva of infected female anopheles mosquitoes, also called “malaria vectors".1 When a human being is bitten by a malaria vector, the parasites are introduced into the victim’s bloodstream and travel to the liver, where they begin to reproduce. Symptoms appear soon thereafter.

Prevalence

In 2015, Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 90% of the world’s malaria cases and deaths. However, South-East Asia, Latin America and the Middle East are also considered areas at risk. Essentially, wherever warm conditions and stagnant water are required for mosquitoes to thrive exist, malaria is an ever-present danger. In fact, the WHO cites 91 countries and areas with ongoing malaria transmission.1 The world therefore cannot afford to be complacent about this crippling disease.

Symptoms

Malarial symptoms usually first appear between 8 to 25 days days after mosquito bite. The initial signs of illness often resemble flu-like symptoms such as headache, body aches, vomiting and fever. Malaria is therefore often misdiagnosed as influenza, which can be a fatal mistake as it requires very specific types of treatment. In later stages, malaria presents itself in jaundice, convulsions and paroxysm, the latter referring to a cyclical occurrence of cold sweats followed by high fevers over two-day cycles.

If left untreated or in cases of severe cerebral malaria, seizures or coma can occur. It is therefore vital that malaria is accurately and swiftly diagnosed and appropriate treatment administered.

Diagnosis and Treatment

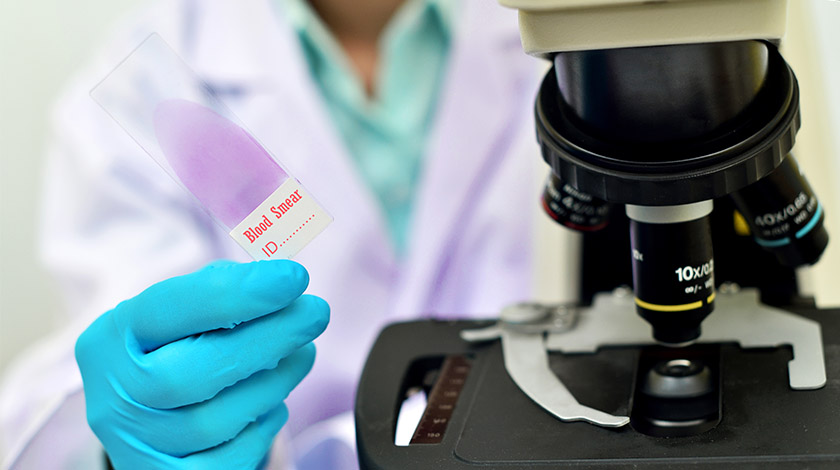

WHO recommends that all cases of suspected malaria be confirmed using proven methods of parasite-based diagnostic tests. Physicians will often administer a malaria diagnostic test on the basis of one of the following high risk factors— enlarged spleen, low number of platelets, and history of recent travel to malarial zones. The two most common diagnostic methods are microscopic analysis of blood sample films or antigen-based rapid diagnostic tests.

The most efficacious treatment for malaria is usually combination therapy which includes an artemisinin compounded with either sulfadoxine or mefloquine. In areas where artemisinin is only sporadically available, combination therapy comprising doxycycline and quinine is also common.1

Prevention

Unfortunately, there is no vaccine available for malaria. Malarial prevention therefore focuses on bite prevention. Malarial risk is highest in densely populated areas combined with high anopheles mosquito population density, as mosquito to human transmission (and vice versa) is most prevalent in such places.

Therefore, there are two key approaches to preventing malaria. The first is to lower mosquito populations by reducing the incidence of stagnant water. The second is to lower the incidence of mosquito bites, by employing residual mosquito sprays and insecticidal nets.

Antimalarial medicines can also be used to prevent or interrupt malaria and are recommended for travelers and pregnant women living in moderate-to-high transmission areas.1 The long-term use of these preventative drugs is not physically or financially feasible for residents in malarial zones; their efficacy, therefore, is largely limited to short-term visitors to these areas.

WHO in action

In recognition of the formidable obstacles to the ultimate goal of global malaria control and elimination, the Global Technical Strategy for Malaria 2016-2030 was initiated by WHO and adopted by the World Health Assembly in 2015. The strategy aims at providing a framework for all endemic countries as they work towards four crucial goals:2

- Reducing malaria incidence by at least 90%

- Reducing malaria mortality rates by at least 90%

- Eliminating malaria in at least 35 countries

- Preventing malaria resurgence in all countries that are malaria-free

The initiative will undoubtedly form a pillar for the worldwide effort against this debilitating disease, in the hopes that we might one day see the dawn of a malaria-free world.

Resources

- Malaria Fact Sheet. World Health Organization. Visited 07 March 7, 2017.

- Global Technical Strategy for Malaria 2016-2030. World Health Organization. Visited 07 March 7, 2017.